It seemed to me as if they had attained something and

Were looking to light and hope,

I don't know why.

Margarite September 1921

The shocking message of cruel finality is on a scrap of paper. It is pasted in Grandmother's special album. Underneath there is a note in Anna May's still clear handwriting:

"Telephone message brought by Canon Jose, Canon of Christ Church Adelaide. Communicated to him by Father Falvey, St Dominic's Priory - to whom the War Office had first sent it".

In a hastily pencilled scrawl the message recorded that Frank had been KIA (Killed in Action) on 26 August 1918, that Frank was 2802 Lance Corporal in 43rd Battalion AIF, that A.M Dealy was his next of kin (mother), that Frank was "RC" and May's address was 45 Brougham Place North Adelaide. It was dated 9 September 1918, 14 days after the KIA.

For a mother still grieving for her youngest son this message must have been simply awful.and as a means of conveying such dreadful news, it seemed cruel and unfeeling.

What words could Canon Jose have used to break the news to Grandmother when he delivered that piece of paper? Even the most carefully chosen could not reduce the hurt and the sense of huge dismay, and despairing emptiness. Even at this great distance of time, reading the bald, scrawled and barely legible wording arouses feelings not just of grief, but also of impotence and unreasoning anger. The first message below was written in pencil on a page torn from a field note book and was short:

How could the loss of that so promising life have been dismissed with such seeming callousness? Why did it have to come by such a circuitous route; why was the Catholic establishment the first to receive it and not the family? Was the Catholic establishment afraid to deliver the message itself and so chose to use an Anglican priest instead? Why to have taken so long?I suppose it was meant to comfort and maybe in the context of that time it did.

But it seems to me to have been patronizing at the very least, and at worst clumsy in its emphasis on Catholicism. Grandmother was brought up an Anglican and staunchly remained so for all her life; but that seems to have been of no consequence. Her marriage to Thomas Kirkman Dealy, a Catholic of Irish/Yorkshire descent, meant that her children had to be brought up as Catholics. Nevertheless, Grandmother was strong in her own faith. I suspect that her own independent nature and strong intellect would have found the letter hard to accept not just because of its sad news, but also because of its implicit and tactless, almost arrogant assumption in the rightness of the Catholic Faith to the exclusion of all others.

Within the next few days, weeks and months Grandmother received depressing confirmation by way of various letters. Initially the missives were sparse in the details. The next letter of note was signed by a Lieutenant in the local Military District:

Again, for its time I suppose it was meant in good faith and as a token recognition of the sacrifice that had been exacted. But such a letter, signed by a minion at the behest of a senior in the military hierarchy to convey the regrets of a remote monarch and his consort and the Commonwealth Government seems just for the record and for form.

For Grandmother the loss of her sons represented 100% of her total contribution to the War. For Australia the loss of her two sons were less than .0001% of the total killed. I suppose the letter from the 4th Military District was sufficient acknowledgement of the loss in the context of the whole but for Grandmother the letter must have been cold comfort indeed.

A third letter was signed on 2 November 1918 and came from the State Premier's Office:

The author appears to have signed the letter personally. Perhaps that demonstrated an earnest of good intentions and official regret. In the context of the time I suppose it was the least that Grandmother could have expected, but the pompous convoluted language of officialdom would have been hard to take.

Particularly hard to take was the fact that the letter was almost a repeat word for word to one she had received in March 1918, barely 5 months earlier shown below. It must have been a bitter "de j'a'vu" It came from the same person:

In the event thboth messages seem to lack sincerity because they were so evidently a part of the endless repetition of the same formula to countless other homes:

At least the date on one had been typed in rather than stamped, but the unfeeling nature of the official machine is very evident.

But another letter received in March produces a similar impression of an official bureaucratic machine conforming to form and sending messages purporting to be sympathetic.

There are significant differences between the two letters, I suppose one was the version for the many, many other ranks who died. The other slightly more exalted version being that for commissioned ranks, but perhaps just for the junior orders. One wonders what sort of letter was written to the next of kin of officers of more exalted stations like Colonels and above. Even in death the class ranking system so fundamental to the British of the time had to be observed.

A later letter gave some details of what happened on the fateful day. The copy in Grandmother's album appeared as:

Henry Ough was Grandmother's father and one has to assume that she would have received the original letter but that has disappeared. Perhaps she threw it away in disgust. The words are those of remote bureaucrats dealing with the harsh facts of life, or rather of death.

An earlier letter from Grandmother's sister Marion is much better and has obviously been written by someone who cared. Marion wrote it from her home in Woolwich Arsenal in London:

Marion's letter showed all the affectionate support and empathy that Grandmother so needed at her time of trial. Doubtless she received other kind and supportive messages in the same vein from her other four sisters and two brothers but there are no copies in her Black Box.

But the Box contains all sorts of other things that followed the loss of Sydney and Frank. In her sadness and attempts to cope she and Thomas must have kept everything they received during that melancholy period. The collection includes newspaper notices and short reports, items from school magazines, items returned by the military, post cards and letters, certificates. The following table records some of this sad memorabilia.

Date Item Comment

21 December 1918 China Mail Hong Kong The Late L/Cpl Frank Dealy AIF

21 November 1918 The Advertiser Adelaide Legal Notices

15 October 1918 The Advertiser Adelaide Roll of Honour

4 December 1918 The Times London Killed inAction

30 November 1918 Sheffield Daily Telegraph Dealy - KIA

6 December 1918 Stamford Mercury and The Lincoln Rutland Ditto

The Black Box contains a collection of postcards from Thomas Kikman Dealy sent in August and September and October 1919. He must have obtained an appointment as a tutor in the University of Grenoble in the Alpines district of France because he mentions that he has arranged a place for Margaret at the local Lycee for girls and that he is taking rooms in the town. There are also instructions for the transfer of three boxes to be sent to him there by " Petite Vitesse".

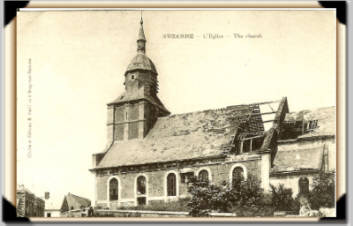

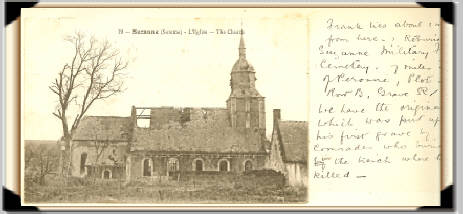

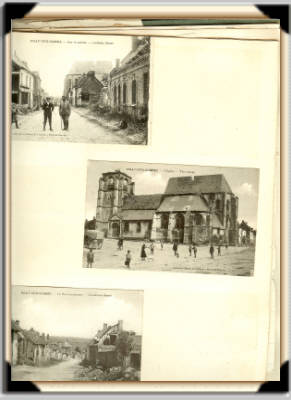

The pictures on the postcards (I found 22 of them in the Box) provide a contrast to the messages he scrawled on some of them for May or Margaret. The photographs all show stark scenes of the war ravaged city of Reims, and towns and villages in the valley of the Somme.- Albert, Bray-sur-Somme and Suzanne. He must have decided to see for himself and alone the battlefields where Frank was lost and then to carry on to Grenoble to start his new job. The postcards were posted in Reim, Paris and Grenoble providing a record, at least in part of his wanderings through the still scarred areas. There are several pictures of Bray-sur-Somme where Frank had set out on his last day and of Suzanne near where he had been buried. It isn't clear from those few glimpses whether or not he had managed to find the grave because it could still have been where Frank had fallen and as yet not identified and transferred by the War Graves Commission. In fact Thomas is silent on that aspect and leaves no record of his feelings. It must have been a sad journey for a man who had spent so many years alone separated from his family and especially his two sons for whom he had done and cared so much

On the 19 August 1919 he sent three cards from Reim with no messages. A day later he was in Paris and wrote cryptically to Anna May:

Thank you for Cook's letters. The three boxes should be sent by Petite Vitesse and not otherwise. The heat here is intense and does not decrease. There is however a little breath of air in movement, but not much. Love T.

On the 7 September 1919 he wrote at greater length to Margaret from Paris:

Dearest Margaret, I am going to try to find dear Frank's grave on Tuesday, the day that this letter (postcard actually) should reach Torquay. I will tell you all about it next week. On Friday or Saturday I leave Paris finally and on my way to Grenoble will call at Lyon to see Mounsieur Brun who has been very ill. I hope to find him in better spirits because he is staying a while in the mountains, the Alps, not very far indeed from Grenoble. My letter from next Sunday will be written from Lyons. I am looking forward to the time when we three shall be together again in Grenoble. I kiss your dear hands. Ever your affectionate Daddy.

On the same day he wrote to Margaret again:

Dearest Margaret, You are a sweet dear girl and I thank you ever ever so much for these lovely little things in porcelain you have bought for my rooms in Grenoble. You are evidently trying to spoil me, you and Mammy between you. Thank you so much once more. I am extremely fond of you. Pray for Frank and Sydney and for me dear. Much love from your affectionate Daddy.

There is a partial message on another post card written later and presumably from Paris and to Margaret:

changed for the better. It is not as hot as it was. Grapes are five times as much here as in Australia so I don't eat them often. Please remember me to the Sisters who are so good to you. It comforts me a great deal to know that you are in such good hands. Give Mammy a big big kiss and a hug from me. I kiss your dear hands and remain your ever affectionate Daddy

The last card in the series, again to Margaret gives her some apparently startling news about her own future. It was written from the Pension Mornier 8, Rue Voltaire Grenoble:

Bray was the village from which Frank set out on 28(?) August 1918 at 5 in the morning, the day he was killed. The next PC shows the battered church of the tiny village near which he was actually killed and near which also he is now buried. Thank the Sisters dear very much for me for all the many acts of kindness they have shown to you. Fancy, on November 1 you will be going to the Lycee here with French girls..

The messages evoke a picture, albeit fragmentary, of an affectionate, sad and caring man doting on his daughter of just 12 years, but seemingly with somewhat distant relations with his wife. His spirits must have been low at that melancholy time, especially following his wandering through the devastation of the Somme battlefields to try to find his son's grave. It is not clear at all whether he ever did find the grave on that trip.but there is a note in the album next to picture of the church in Suzanne:

Frank lies about a mile from here, reburied in Suzanne military cemetery, 7 miles NW of Peronne Plot 2 Row B, grave R. We have the original cross that was put over his first grave by the comrades who buried him in the trench where he was killed.

There is also a picture of a French cemetery in the tiny village, so I suppose he must have found it.

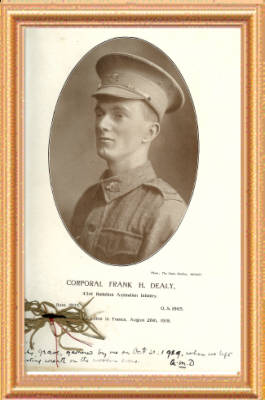

There is a brief note under Frank's picture in the album in Grandmother's hand.

Piece of grass from Frank's grave gathered by me on October 30th 1919,when we left an ever lasting wreath on the wooden cross AMD.

The piece of grass is tied up with a pink silk and is pinned to the photograph. From this it seems that AMD on her way to Grenoble and must have followed in Thomas's footsteps. It is not clear whether Margaret Mary was with her, but it seems reasonable to assume that she was. At any rate she, Margaret, was due to start at the Lycee de Jeune Filles in Grenoble in November. But it seems sad that the circumstances forced Grandmother and Thomas to visit the grave of their eldest son separately.

Grandmother must also have been to Sydney's grave before leaving England as there is a photograph of the headstone showing the additional inscription to Frank's memory.

There is a formal letter from the Imperial War Graves Commission dated 19 December 1919 Frank's remains had been exhumed from the initial grave and re interred with due ceremony under a wooden cross at the Suzanne French Military cemetery. That must have been the grave seen by both Anna and Thomas.

Later in March 1920 all wooden crosses were replaced with permanent memorial tablets by the IWGC and the originals returned to the next of kin. From a pencilled note in TKD's handwriting it is clear that the cross was returned to him in Grenoble. But what happened to it afterwards remains a mystery.

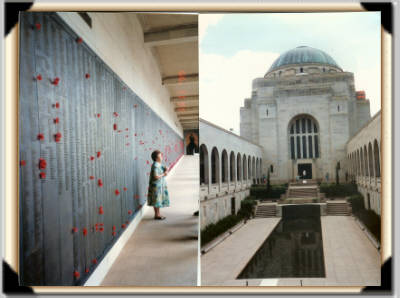

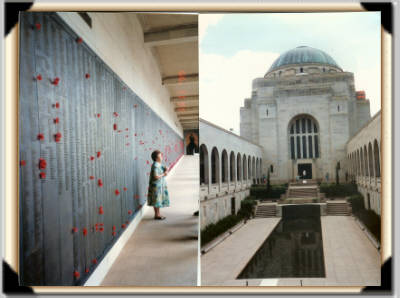

I visited the Suzanne Military Cemetery in 1988, 70 years after Frank's death. I found the cemetery still very well cared for. It is, of course just one of hundreds of others established and still looked after by the War Graves Commission as memorials to the thousands who fell.

Suzanne Military Cemetery No 3 is set on a ridge on the edge of a large field by the road between Suzanne and Maricourt in the province of Picardy. There are few trees to be seen nearby giving an impression of bleakness. Yet it was quiet…the road being almost a country lane with not much traffic. There is an atmosphere of tranquillity and loneliness accentuated by the low stonewall that surrounds the grave yard and the single Great Cross at the entrance. The WGC information booklet contained the following entry: Suzanne Military Cemetery No 3 is North of the village. It was originally a French cemetery (Cemetiere Mixte No 3 De Suzanne), but after the Armistice the British graves were concentrated into it from the battle fields North of the Somme and the French Graves were removed. The cemetery now contains the graves of 102 soldiers (and sailors of the Royal Naval Division from the United Kingdom, 28 from Australia, 8 from Canada and one German. The unnamed graves are 42 in number.

Frank's grave is the first in Row B of Plot II. Beside his are the graves of his two companions Theobald and Peters. The particulars of all three, like those of all the others buried in the cemetery are in the Register. The entry for Frank reads:

“ DEALY, Lce Cpl F.H. 2802 43rd Battalion Australian Infantry 26 August 1918. Age 23.Only surviving son of Thomas K. Dealy (late Headmaster of Queens College Hong Kong and A.M. Dealy of 19 rue Voltaire, Grenoble, Isere, France B.Sc. II B 1.

The details of other comrades in arms who share the peace of this place provide a revealing commentary of the history of the war and the events that took place in this small part of France. There are two infantrymen of the 13th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles who died on 1 July 1916 no doubt one of the thousands who died on that first appalling day of the Battle of the Somme.. There is another of a Rifleman of the 9th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade who died on 8 April 1918, fallen during the last of the great German offensives in the war.the offensive that resulted in the loss to the Allies in just 2 months of all the land they had fought over to win in the previous three years at such unimaginable costs. A Canadian Subaltern of the Post Office Rifles lies buried a few rows down, killed on the same day as Frank, a comrade in arms from another far away country involved as part of the British Fourth Army in one of the last Allied efforts that finally pushed the Germans to surrender only 13 weeks later.

The men buried there from the United Kingdom were casualties not only of the final battles in 1918 but also of those that took place in earlier years. But the sadness of the losses in 1918 is made all the more poignant by the short period left before the guns were to fall silent. Most of the Australian and Canadians in the cemetery fell during that last great Allied offensive in August and September 1918.

Apart from several who fell in 1916 during the Battle of the Somme there are others who fell in 1917. They had served in a variety of regiments and services. On just 4 pages of the cemetery Register the roll call is like a microcosm of the British Army and included men from the Royal Engineers, Royal Field Artillery, Seaforth Highlanders, Royal Army Service Corps, Kings Royal Rifle Corps, the London Regiment, The Middlesex Regiment, The Gloucestershire Regiment, The London Rifle Brigade, Northumberland Fusiliers, the Devonshire Regiment, Royal Australian Engineers, and the 17th, 38th, 40th 42nd and 43rd Australian Infantry Battalions.

One wonders how it was that all these men from so many different parts of the Army, who had lost their lives at such widely different times and in such a scatter of places found their final resting place in this quiet and relatively remote place. It is almost as if the hand of fate yielded a brush and pan to pick up all this small detritus of war in some random way to put it down and bury it for ever. But not without feeling......close by the graves is a stone tablet with the message:

"The land on which this cemetery stands is the free gift of the French people for the perpetual resting place of those of the allied armies who fell in the war 1914-1918 and are honoured here."

That message and the simple, cared-for dignity of the place is probably as much as can possibly be expected to commemorate these men.

There is one other letter in Grandmother's box that provides another perspective of that place and time and its impact on people close to the family. It describes a visit by Margarite to Frank's grave in September1921. Who she was is a mystery. She wrote it from Hemstal Road in Hampstead, the address where Frank spent his last leave in England in March 1918. Perhaps she was his girlfriend? Anyhow, she wrote it to Vera and again it is not clear who Vera was but the text suggests that this may have been her nickname for Grandmother Dealy. Her letter is a moving commentary on which to conclude this record of a most melancholy period.

REST IN PEACE

Copyright of all parts of this site is owned by Martin Ough Dealy

This page last modified on Friday, 20 September 2024