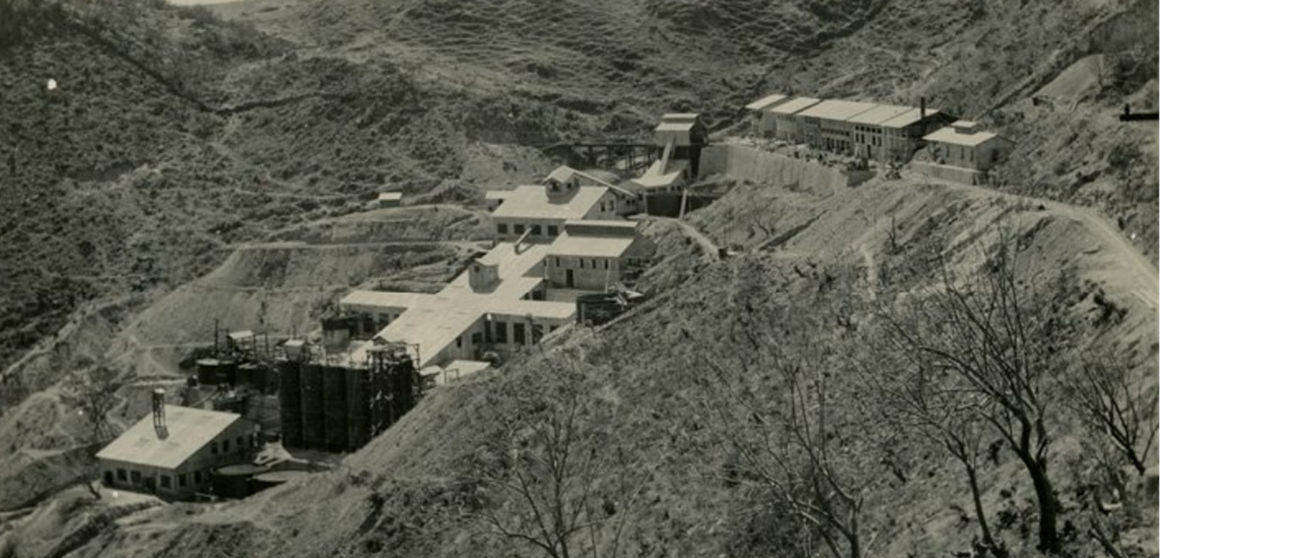

The year was 1936 when the Santa Gertrudis mill and the Dos Carlos mine were still active and producing large amounts of silver. The mill and the mines were British owned and operated, but located at an altitude of over 8000 feet in the foothills of the Sierra Pachuca a branch of the Sierra Madre Oriental in faraway Mexico . The rough and sometimes wild capital of the State of Hidalgo was the mining town of Pachuca just a few miles away to the west.

The mill lay protected from bandits and other avaricious men behind high stone walls topped with broken glass set in concrete. The mine itself was similarly protected but a short distance away. In those days between the world wars, the area was relatively unpopulated dominated by semi desert arid land of rolling hills bounded to the north by high mountains of the Sierra Pachuca. 1936 was just a short two decades from the earlier Mexican Revolution and the times were still unsettled and dangerous.

There were several mines operating then with names like Minas San Francisco, La Blanca Dos Carlos San Guillermo and San Jose. These were solitary establishments some dominated by Cornish pump houses and chimneys. Dos Carlos Mine was probably the most active and productive and it is in this mine that this story is based.

The mine was deep and because of this, providing sufficient air to supply the miners working underground was a problem. It was a hard rock mine, but several of the workings were through poor ground requiring extensive wooden structures and props to prevent rock falls. Large fans sucked air through the main mine shaft. Others blew air along the tunnels to an exhaust shaft some distance away. The mine had been modernised after WW1 and all the machinery was electric.

Unlike other mines to the north of the district Dos Carlos was a fairly dry mine and did not suffer from flooding. In fact it was so dry that the timber props and supports were tinder dry; a major and ignored fire hazard.

Attitudes to safety were lax in those days and there were no rules against miners smoking neither in the mill on the surface or in the mine itself.

And so the inevitable happened.

Somehow, no one really knows how, something set off a fire deep in the mine. Because no one had noticed it in time, fanned by the generous air supply, the fire quickly got going, became uncontrollable and set many of the wooden support frames ablaze. By the time the alarm was raised, smoke was pouring out of the exhaust shaft and many of the miners underground had become disoriented by smoke, or trapped in blocked tunnels by fallen debris. Most barely escaped to the lift cage in the main shaft. Of the 110 men in the shift underground 102 managed to get to the surface leaving 8 unaccounted for.

Fortunately the head of the underground rescue team, Andrade, was a conscientious hard working and determined man. A Mexican he was well respected by the traditionally close-knit community of miners. An engineer he had worked for Santa Gertrudis for many years. He knew the mine in all its subterranean complexities and immediately started doing his best to find the 8 missing men.

But he had to wait until the underground fires had burnt out. Fire fighting had been hampered by the lack water and the rabbit warren of tunnels many blocked by rock falls and ruined machinery hidden in thick choking smoke. The failure of the ventilation system meant that lingering smoke underground was a serious hazard, confusing and disorienting the search team who could barely breathe in the noxious fog.

Fortunately they had special breathing equipment that enabled them to get into the mine and survive, until their clean air supply was exhausted. And so they searched every nook and cranny. This took hours but in the end when the exhausted team finally surfaced to face the anxious crowd above they could only report failure. There was simply no trace of the missing men, no sign whatever, not even their bodies.

Andrade was not a man who gave up easily. After a short rest break and a scanty meal he went back into the mine again with his team. With better lights this time, electric torches rather than the old-fashioned acetylene miner’s lamps, they scoured every part of the mine that they could access. But the result was the same – nothing anywhere – no sign of life or death in any part of the destruction.

Exhausted they returned to the surface.

Mostly of Indian Aztec and Toltec descent the mine workers, despite their historically enforced adherence to the Roman Catholicism of the Spanish conquerors, still clung to the myths of their forebears. They stubbornly believed in the remnants of the religions of their ancestors. They still believed their cruel gods like Huitzilopochtli - God of War and Tlaloc - God of Rain and Sun. But it was at times of disaster, like this one, that they turned to Tezcatlipoca - God of Destiny and Fortune.

Andrade, himself of mixed blood, was well aware of the superstitions of the miners and their belief in the influences of the supernatural. It was during his exhausted sleep the following night that he dreamt. He heard the voice of one of the missing miners a man without hope and facing the certainty of death praying to Tezcatlipoca, pleading with him to look again. The pleadings were incoherent the only words Andrade remembered when he woke up in a sweaty delirium were something like “busca otra vez por dios”. “Somos en el parte de la mina mas fondo” and “escalera de pollo”. “ “sed” and “ambre”

Of course, being Andrade, he determined to have another go. Quickly reassembling his reluctant team he persuaded them to follow him once more into the depths and gloom of the now destroyed, still smoking and abandoned mine. This time they had something new to look for and a vague idea where to find it - in the deepest part of the mine.

After getting past a partially blocked tunnel they headed down in the stygian gloom picking there way through the charred timbers and burnt machinery. Every so often they would stop to listen. All they heard was the odd crackle of still burning wood, the distant echoes from the main shaft and their own heavy breathing. This preyed on their superstitious fearful minds. Andrade had to egg them on to make one last attempt to reach the lowest part of the mine.

Then came a shout from one of the team who had bravely gone ahead; he had found the charred still smouldering remains of an old fashioned mine chicken ladder leading upwards on one side of the tunnel. This was the thing that Andrade’s dream had told him to look for!

At great risk to himself Andrade climbed up. At the top he found a small entrance to one of the escape caves that had been dug by the miners as an unofficial unregistered sanctuary. Poking his torch and head through the hole he saw the staring eyes and exhausted faces of the 8 missing men.

You dear friends can imagine for yourselves the happy ending to this near tragedy.

But Andrade swears to this day that his dream was true and that it had strengthened his belief that the ancient gods of the Aztecs still held sway and that they were not all demanding of human sacrifice.

Copyright of all parts of this site is owned by M.& M.M. Ough Dealy

This page last modified on Sunday 5 February 2023